Before “fake news,” there was “fake data.” And in 2002, Hamilton was ground zero for one of Canada’s biggest scientific frauds. It makes for a scary story that still resonates today.

In the late 1990s, Fine Analysis Laboratories Ltd. (Fine Analysis) was every consultant’s dream partner: accredited, responsive, and cheap. Founded by Hamilton brothers, the company rose from a one-desk startup to a multi-million-dollar empire testing everything from drinking water to environmental samples to pharmaceuticals.

The media initially called it “a made-in-Hamilton success story.”

By 1997, Fine Analysis was boasting $5 million in annual revenue and planning a $7-million, 90,000 ft2 (8,360 m2) new facility. They promised “science at scale” and pricing that crushed the competition. But, as ghost stories warn us, even when everything looks fine – sometimes there’s a spectre lurking just beneath the surface

In 2001, Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment (MOE at the time) started to notice something that didn’t add up — literally. Patterns emerged in the data that didn’t make sense. Some results were just too perfect.

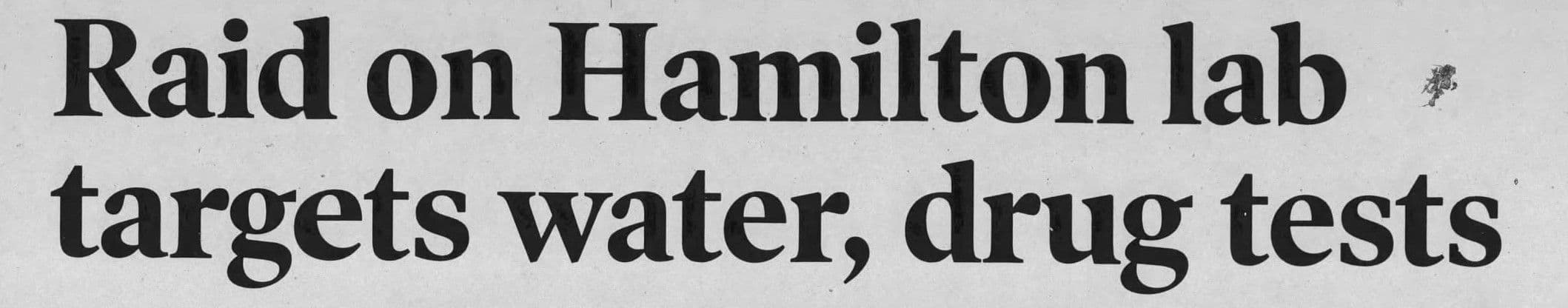

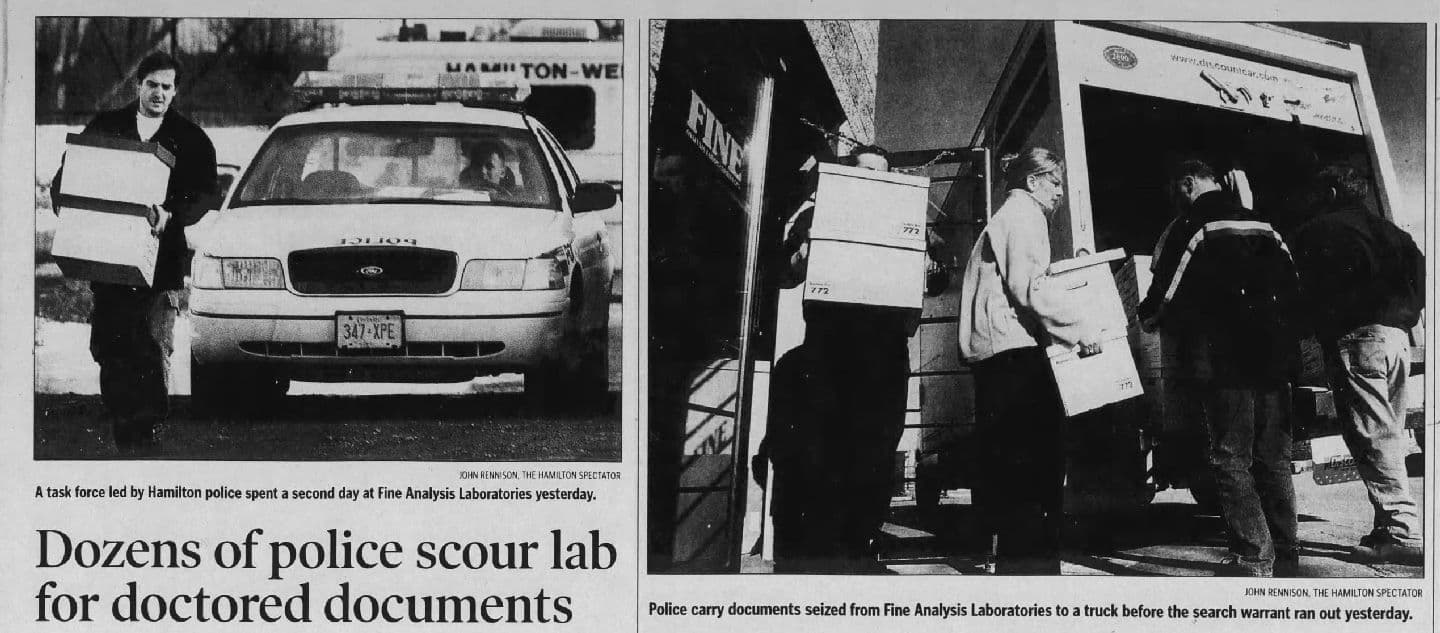

On a cold February morning in 2002, 80 police officers and environmental inspectors swarmed the lab’s headquarters with warrants in hand for a three-day search of records and equipment. The Hamilton Spectator headline the next day screamed:

The allegations? That Fine Analysis had forged thousands of Certificates of Analysis, the official documents that certify the quality of water, soil, and other samples as safe.

Authorities claimed some results were fabricated outright — the numbers had simply been made up.

“It’s someone working to save money,” said one investigator. “Somebody who didn’t care — or didn’t understand the importance of the work — decided they could get away with not doing it.”

The scandal’s reach was staggering:

- Municipalities like Waterloo, Brantford, Parry Sound and others cut ties with Fine Analysis after discovering conflicting results in their potable water tests.

- Philip Services Corp. found that Fine Analysis had mislabeled hazardous waste as non-hazardous, including samples contaminated with toxic heavy metals.

- 50 pharmaceutical companies were told by Health Canada to check their records.

Some companies quietly prepared to pull products off the shelves if the test results proved to be fake. One pharmaceutical insider put it bluntly:

“Now everything they’ve done for us will be in question.”

The Ministry of the Environment quickly pulled Fine Analysis’ accreditation. Health Canada began auditing drug approvals. And Hamilton’s mayor assured citizens that city water was safe — while quietly calling for “a complete overhaul of lab oversight.”

After two years of investigation, the truth was undeniable. In early 2004, Fine Analysis pleaded guilty to conspiracy to utter forged documents and falsifying environmental and pharmaceutical test data. Judges reportedly found that their data were “routinely [and] deliberately… falsified.” The Hamilton Spectator reported “Results routinely altered; sometimes a ‘test’ was done just by smelling a sample”.

The sentence?

- The company was fined $5 million, later increased to $5.5 million after additional counts were added.

- A senior staff member got nine months of nightly curfew, and two others were sentenced to community service.

- One of the co-owners received two years less a day of house arrest and a court-ordered curfew.

- The other co-owner faced a perjury charge for statements they made under oath during the proceedings.

And the final twist worthy of a horror movie? Before the court could seize company assets, Fine Analysis sold its land and buildings for $1.8 million — leaving the $5.5-million fine unpaid to this day.

The Hamilton Spectator headline said it all:

What makes this story so chilling isn’t just the fraud — it’s how believable the lies looked. The reports were polished, the data neatly formatted, analyst’s signatures were attached. Everything about Fine Analysis shrieked “trust us.”

Back then, the danger was fake data on paper.

Now it’s fake everything — deepfakes, AI-generated news, synthetic reviews.

Different platforms. Different age. Same problem.

In an era where you can’t always trust your feed, or even your eyes, skepticism isn’t cynicism — it’s self-defense.

If a deal, a dataset, or a dashboard looks too perfect, ask for proof. When the price seems “too-good-to-be-true”, sometimes the only thing being tested is our trust.

That may sound bleak — but it’s really a challenge. It means we have to be smarter than the scammers, whether we’re reviewing lab data or scrolling through our feeds.

Fine Analysis may be long gone, but the lesson lingers: the real horror story is when we stop asking if what we’re seeing is real.